That heightened sense isn’t developed so much by traveling the world as by remembering to focus on where we stand. Proust once wrote, “The only true voyage of discovery…would be not to visit strange lands but to possess other eyes, to behold the universe through the eyes of another.” Lesser known is Jane Austen’s affinity, particularly for the large rambling hedge maze at Sydney Garden in Bath, England (since gone), where she wished to walk every day.

Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges’s peculiar love of them is well known – he wrote once of gods who lived in them, encircled by forking paths. Literary figures also embraced the labyrinth.

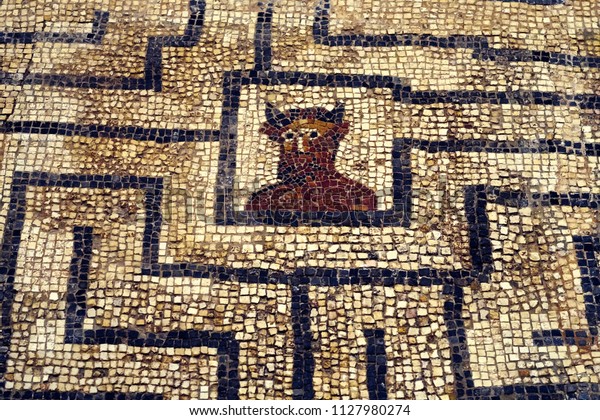

Daedalus famously used one to trap a minotaur. (Strabo called it a wonder of the world.)īefore taking to the high seas, Scandinavian sailors built stone labyrinths to trap sinister winds that might follow them. They have been used as pleasure walks, meditative journeys and symbolic life-into-death pilgrimages.Ĭlassical thinkers Herodotus, Pliny and Strabo each praised the Egyptian maze of Middle Kingdom that Pharaoh Amenemhat III constructed in the 19th century B.C. Traditionally, they kept evil in and invaders out. One can be found in a petroglyph on a river shore in Goa, India cut into the stones of Ireland’s many medieval churches and arranged in a contemporary land-art installation at Lands End in San Francisco. These mazes have appeared in various corners of the world throughout history. Labyrinths, however, can remind us how it’s done. The wonder of travel lies equally with adventure and misadventure – there is nothing like getting thoroughly lost in a riddling country or culture that is not your own.īut it is hard these days, with our ultra-planned excursions, fixers and 4G service, to get properly disoriented.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)